I I just lost my girlfriend, because that song isn’t mine anymore.

— Trent Reznor, on Johnny Cash’s cover of “Hurt”

Adaptations. Reboots. Remakes.

At this point, they’re all Hollywood ever releases. At best, they’re somewhat successful, preserving the essence of the original while alienating only hardcore fans, like the 2003 Italian Job and the 2010 True Grit. At worst, they’re reheated cash grabs that strip the soul of the original, presenting no real reason to exist, like the 2019 Lion King.1 Understandably, a lot of people have turned against the idea of cinematic adaptations.

But I find the process of adaptation to be inherently intriguing. How does a story change from one director to another? How does cultural context shape and reshape the story?2 How does adaptation preserve, or distort, the themes and message of the story? And, thorniest of all — can a remake ever surpass the original?

I’ve thought about these questions long and hard, partly because of the state of entertainment today, partly because of my longtime ambition to reboot a certain nostalgic cartoon from my childhood.3 But I’m thinking about them much more because recently, an adaptation of my own work was made. And man, it feels weird. But to explain why, I have to look back at a very embarrassing time in my life.

Drawing the Line:

During high school, I took two years of film study class. I knew nothing about filmmaking, but I quite liked movies, and getting to watch them for school credit sounded like a far better elective than psychology or whatever else was on offer. Besides, my best friend at the time, an aspiring filmmaker, was taking it, so why not give it a try?

This was not a happy time in my life, for painfully cliche reasons. My family had left California for Seattle, and I was not thriving. The weather was always gloomy, and I was entering my new high school in sophomore year, making it hard to make friends. I was also dealing with a nasty autoimmune disease and some untreated mental health issues on top of your usual teenage hormones.

But I can’t act like external factors were the only reason why my life sucked. I seemed to think that performative misery made me seem sophisticated, when it really just made me unpleasant and genuinely miserable. I was prickly and hostile to most people — partly as a defense mechanism, partly out of sheer pride. I do not like the person I was at age seventeen all that much. Does anyone?

Film study was a rare bright spot in all this. The teacher, who also taught my English class, was one of the best I’d ever had — he was a hippie type who was more than happy to indulge my rambling asides in class discussions. He showed me that film was more than Marvel, adding Alfred Hitchcock, Richard Linklater, and Stanley Kubrick to the theater in my brain.

He also saw that writing was becoming an emotional outlet for me, and he encouraged me to lean into it. I wrote officially sanctioned 1984 and A Doll’s House fanfiction for that class, and he loved it. I think I partly credit him with the fact I finished my first ever novel during high school.

So, when the second semester of class moved from just watching films to making them ourselves, I was quite happy to take on the role of screenwriter.

For our narrative film, my aspiring filmmaker friend was very interested in the idea of The Little Shop that Wasn’t There Yesterday, a magical, mysterious place hawking dangerous wares. I ran with this idea, making the shop a metaphor for drug addiction and the Shopkeeper into a violent, dangerous entity who is strongly implied to be Satan. I created the concept of a “line” of wickedness that the protagonist somehow crossed, allowing the Shopkeeper power over his soul.

I cast myself as the Shopkeeper, deciding to give him a camp, effeminate manner and a British accent. My performance was really a dime store version of Jeremy Irons’s Scar mixed with Ian McDiarmid’s Palpatine, with maybe a smidge of Robert Carlyle’s Rumpelstiltskin thrown in for good measure. Both my writing and my acting were defined by one thing: ham. It was over-the-top, cheesy. But I took it very seriously.

In hindsight, I think the film’s themes were borne out of my mental health issues in a way I didn’t fully credit at the time. The protagonist was a loser whose life only gets worse, reflecting my anxiety about oncoming adulthood and life in the first Trump era.4 The Shopkeeper served as a righteous avenger, not only killing the protagonist but making sure he knows he’s a worthless human in his last moments. I think I was worried the same thing would somehow happen to me. And contrary to what I said at the time, casting myself as a Satan analogue was not just “because the villain is cooler.”

I quite enjoyed the filmmaking process. We all pooled everything slightly creepy we owned to add it to the shop for a fun evening of set-building. We traded light-hearted barbs over the lines we flubbed, congratulated each other when we got it right. We experimented with all kinds of filmmaking techniques, from Dutch angles to smoke machines to greenscreen eyes. We made fun of each other for the eyeliner we wore for filmmaking purposes. We went out to Kidd Valley or Ivar’s for deep-fried dinner some nights. I’d always had trouble making friends, and it felt nice to be a part of this community.

But despite my nostalgia, I do regret a lot of my behavior on the set of the film. I was convinced I was a uniquely talented auteur writer, and I wasn’t willing to listen to criticism. To quote a certain pink-haired cartoon character, I was “stubborn as a fool.” I was arrogant and domineering towards my friends, and I often got into fights with them. I cringe now thinking about it. Sometimes I was right, but more often, they were.

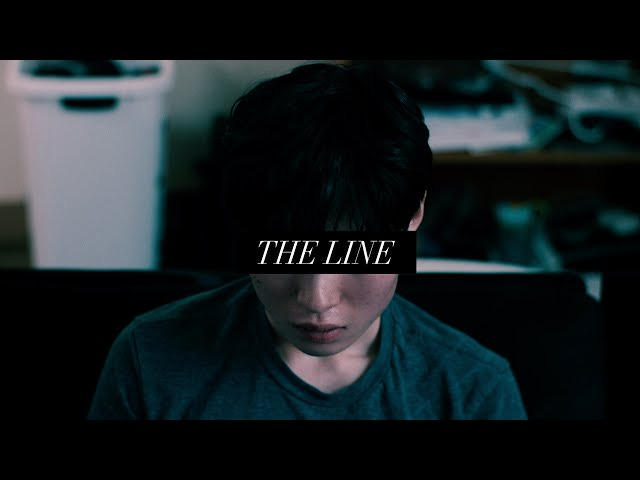

After a grueling month of filmmaking, we had a finished movie — “The Line.” Give it a watch!

At the time, I was very proud of the film. I thought I’d made a scary horror film with something deep to say about modern life. I loved my performance, thought I was hilarious and terrifying at once. My friends had a more realistic view, but I refused to listen to them. We pieced together a silly shared universe for the film, and I wrote some short fiction set in it. I thought this film was the start of something special.

But looking back — this is not good. We definitely made some dopey stylistic choices — the over-the-top lighting, the overuse of Dutch angles, the greenscreen eyes. All that’s to be expected of an amateur filmmaking project, though.

My issues with the script were far less excusable. I thought I was such a good writer, I didn’t need help. But I did. The dialogue now feels overcooked, pretentious, and honestly, painful to read. I was groping at some genuinely interesting ideas, but I don’t think I grasped them at all.

It’s the painful fate of a writer that the better we become at our craft, the more we dislike our earlier work. I now have two full novels, many short stories, and of course, dozens of lion statue reviews under my belt, and I strongly dislike my high school work now.

So, as time passed, as I became a better writer, I didn’t often think about “The Line.”

The Remake:

When my friend called me, almost seven years later, to ask my permission to remake “The Line,” I was a very different person. I had many new scars, but I was a happier person in a far better emotional place.

It was so strange to receive that call and with it, a reminder of the person I used to be, a painful burst of nostalgia for my time creating the film. We’d drifted apart a bit — no big blowup, just a natural consequence of moving away, of life getting in the way of our plans to meet. The bond forged by our collaboration wasn’t as strong as it used to be.

I appreciated that he asked my permission — it was already a bit emotional, having to hand over the reins like this. But I knew this wasn’t really my film. They’d done most of the real work putting the movie together. For that reason, I didn’t hesitate to say yes.

I had a good conversation with the new director a few weeks later, explaining my vision for the character and the film. It was clear that he had some very divergent ideas about what to do with the story. But he was respectful and polite, promising to maintain the movie’s core elements. He brought up some interesting ideas, and I came away feeling good about his plans.

Still, though, in the coming months, as production ensued, as my friends shared set photos, I felt a lot of trepidation. What if they ruined the story? What if they changed everything? What if they made something I hated? For writers, stories are like our children, and we are very protective of them.

On July 6th, the remake of “The Line” was finally released. Give that a watch too.

Did they make too many pointless changes? Did they ruin the core of the story? Did I hate the remake?

No. The truth was far more painful. I liked the remake more than the original.

Grief:

Objectively speaking, the remake is a better-made movie. That’s not surprising — the production values are far higher. The washed-out lighting conveys the menace of the setting much more effectively. The carnival-style music makes for a much creepier atmosphere. The longer length allows more exploration of the protagonist’s lifestyle. The lack of maturity restrictions allows more explicit depiction of drug abuse.

But I’m astonished by how much better this version of the Shopkeeper is. The new actor never flubs his lines, never messes up the timing. He nails both the campy, hammy comedy and the visceral menace of the character, far better than I did. Both his line deliveries and his physical acting convey complete dominance over the protagonist in a way I never could. My Shopkeeper got too loud and shouty at the end, but his maintains a cold, patronizing, and playfully sadistic demeanor even in his final rant.

The dialogue, too, is better. Everything is so much more coherent, flowing much more smoothly than my original lines. The “iconic” moments from my script are largely maintained, yet greatly improved. I particularly noticed how the Shopkeeper’s “mirror” monologue follows a much more logical order, with a much more natural sequence than mine.

The final rant does a much better job of conveying just why the Shopkeeper despises the protagonist so much. Rather than my vague delineation of “the righteous” and “idiots and fools,” this Shopkeeper divides humans into “people” versus “leeches and slugs.” He condemns the protagonist’s laziness and dependence on others, a much clearer rationale and a stronger message than the original film.

Not only is it better — it manages to be better without betraying my original vision. Again, the Shopkeeper is still a campy and comical yet undeniably menacing figure. Most of the best lines of the original are still here, just shifted and recontextualized to be more effective. It’s the same story at the core. If I wrote “The Line” today, it would have looked more like this movie. In fact, the new movie might just be closer to what I hoped my original movie would look like.

And it hurts. It is deeply painful to realize that I am apparently not the best person to tell this story. It makes me feel like my effort was for nothing, if someone else can do a better job. I think self-doubt is a major challenge for any writer, and this experience does not help. My story has been given what it deserved — but I wasn’t the one to give it.

It would be easier if I could hate it, if I could condemn the changes my friends made. But I can’t.

Again, our stories are like our children. To see the remake improve on your story is like seeing someone else be a better parent to your child. It’s a very upsetting feeling.

Joy:

But at the same time, the remake is enjoyable — enthralling even. I was nervous to watch it, yes, but also excited.

It was thrilling to watch a new version of this story. You know how excited hardcore fans get when they see something from the original movie in the remake?5 Well, it’s far more exciting to see your own dialogue like that! I almost clapped, alone in my own room. I haven’t felt this gripped by a piece of media in a long time.

And as humbling as it is to realize I wasn’t the right person to make this, it’s amazing to see my vision fully realized. This is, again, the version of “The Line” I wanted to make. Even if I couldn’t make it, I’m glad it exists.

Let’s put things into perspective. Most people never even try to create anything. They may dream of artistic achievement, but they never paint or write or film anything. And many of the people who do create never receive any validation that their effort is worth it. They slave away at their craft, but they never get any reward for it. They want an artistic legacy, but they’ll never get one.

So, in a way, it is a privilege to have my story adapted. It is a compliment that my friends would want to remake “The Line.” It means they consider the core of my story strong and worth revisiting. This is more validation than many artists will ever get.

I don’t know how successful the remake will be — the YouTube algorithm is a fickle beast. But my “Story By” credit for the remake is still a legacy. This brilliant film would not exist without me. Without the effort and passion I poured into my performance, into my script. In my review of “The Dying Lioness,” I expressed anxiety that I would be forgotten, that people wouldn’t care about my life. Well, thanks to this remake, that fate is just a little less likely.

Besides, it would be selfish and greedy to say my story has obligations to me and my ego. No — I have obligations to my story, obligations to make it the best it can possibly be. For that reason, I could never have refused it the opportunity to be remade if this could improve it. For that reason, I can’t resent the fact that I don’t own it.

Every child must grow up eventually and become independent of their parents. It is only fitting that my story, my child, should also grow beyond me. I wish it, and its creators, all the best — with or without me.

I will not speak on this further now, but consider this a teaser for my review of that movie, coming very, very soon.

The International Baccalaureate has infected my vocabulary with that atrocious phrase

This is also a teaser. For what, you ask? Patience, all will be revealed.

Now I know how it felt to write “World War I” in 1939. OOOOOOF

A surprisingly mature reflection on the conflict between the artist and his/her own work.